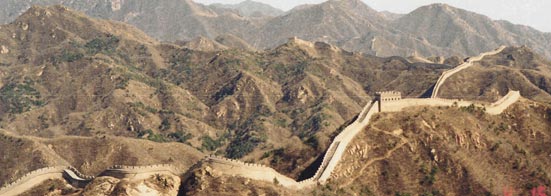

This just in: The Great Wall of China CANNOT be seen from the moon. It’s not even all that visible from closer realms of space, and where it can be seen via a space shuttle flight, so can other human-made objects. Trying to see the Great Wall of China from the moon is like trying to visualize a human hair from two miles away. Besides, the terrain around the Great Wall is so similar in color to the wall itself that differentiating it from such a distance makes it even more implausible.

Up until yesterday afternoon, if you had asked me, “What is the only human-made structure visible from the moon?” I would have promptly and confidently answered, “The Great Wall of China,” likely followed by a smug look subconsciously requesting that you recognize my immense knowledge of all things. I had heard this my entire life. It is such a part of our collective consciousness that this “fact” had even made its way into textbooks at various times.

So, what intense desire drove me to look up this information? My students, of course.

Last week in class, a student put forth the “known fact” that the word picnic came from the phrase “pick a nigger,” and that it was related to the days of lynching when white folks would pack a basket, grab a blanket, round up the kids, and head to a local meadow for some lynching entertainment. I had a faint memory of having heard this before but was not up-t0-date enough on my etymological studies to be able to refute the claim. But I are smart, and I knowed how to look stuff up. Turns out this too is a “know that I know that I know” piece of information that just ain’t true. Picnic derives from a 17th century French word and predates the horrible era of lynching in the United States.

Well, YOU KNOW that I had to share this with my students. The thought of not correcting their belief in a false contention is the stuff of a teacher’s sleepless nights. Urban legends abound; hence, the need for Snopes, not to mention universities. Teaching people to research and ferret out the truth is at the core of what I do.

I would purport that a large portion (maybe in the 90th percentile) of what people believe falls into this because-that’s-what-I’ve-always-heard category. Politics and religion are two areas particularly susceptible to this. I remember when I first read Gilgamesh, an ancient Sumerian tale that includes the story of a great flood. In several ways, this story echos the story of Noah in Genesis, including sending out a raven and a dove to see if the waters had receded. The parallels are not nearly as interesting, however, as the fact that Gilgamesh predates Genesis by about 800 years, and it had been an oral tale long before it was actually carved in cuneiforms on clay tablets. (Gilgamesh reigned as a Sumerian king about 1,500 years before the writing of the earliest parts of the Old Testament; his legend had been told for centuries even before it was finally written “in stone.”)

There are (many) other examples which might create the logical conclusion that the Old Testament should be approached by a metaphysical understanding at best and by a mythological understanding at least.

As I tell my students, I don’t really care what you believe as much as I care that you know WHY you believe WHAT you believe. I encourage them to question preconceived notions, even when at first glance it might seem to shatter the foundations they once thought to be rock-solid. What they just might end up with is an understanding of the world deeper than they could have at first imagined.

Either that or they could just say “Screw it,” and spend their summer vacation at the Creation Museum. Their choice.